September 1, 2009

Supervisor (my City of Boulder planning department supervisor in 1996): I have not seen Owens’ book, so can only comment on the bits you presented. Hard to say who the primary audience is intended to be, but the description seems like old wine in new bottles. I can’t imagine many being swayed either way from the accounts I’ve read. In any event, for a book on this topic to be effective, it would have to be broadly embraced by the general public, because that is where the basis for change originates.

Dom: I’ve not read Owen’s book, either. I read his essay (which I posted on FB in the comment thread following my original post about the interview with him – the interview does a poor job of presenting his viewpoint). After thinking about it later, I think in addition to planners and elected officials, the audience I would think he would appropriately be targeting would be students. I’m not sure about books or opinions being a basis for change. Over the years (and in particular, reading a number of authors on the topic), I’ve come to realize that change in behavior or beliefs is largely driven by material conditions (not to suggest that I’m sympathetic to Marxism or socialism). Behaviors and beliefs arise due to prices, costs, benefits, roads, parking, distances, speeds, economicconditions, etc. An idea can be brilliant, but unless these material conditions promote the idea, the idea will be largely ignored. (for example, water conservation is more common in the western US not because residents there learned wonderful ideas from books or speeches about conserving water, but because water is relatively scarce in the west)

Supervisor: Planners have limited success producing change because they fail to connect with the public, and fail to understand how real change occurs. They talk to the public in arcane, academic terms that don’t address what the average public needs and wants. Planners consistently leave the impression there is something wrong with the way many, perhaps most people live, e.g. there must be something wrong with those people. That is effectively an insult, i.e. the Vermont way of life is “wasteful” compared to NYC, therefore Vermonters are wasteful, and must be bad or inferior people if they don’t mend their ways.

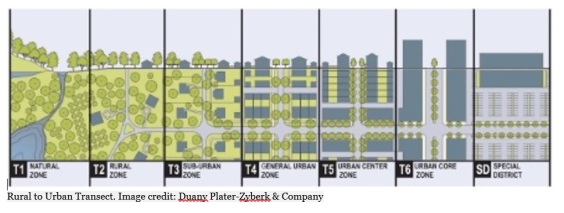

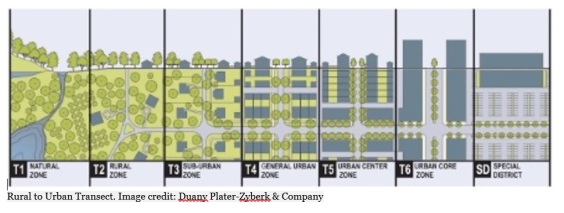

Dom: I agree with much of this, and have spent much time and effort striving to speak (and write codes/plans) in “Plain English.” I sincerely dislike the obfuscation of bureaucratese and legalese. I’ve always sought (and mostly failed) to select words that would better resonate with people (coincidentally, I’m now a “complete streets” instructor in cities throughout the nation, and believe the term strongly resonates with most). You also make a good point about the bad habit many planners have of making people feel like they are doing something wrong, or that they are bad people. This is an important reason why I frequently make it a point to mention and promote, in speeches and writings, the concept of the rural-to-urban transect that new urbanists are fond of, because I believe it is an effective, equitable way to respond to the full set of lifestyle choices. Of course, there are less socially desirable behaviors, and I believe that while such behaviors should be reasonably allowed, they shouldn’t be allowed at the expense of others.

By the way, I think there is a place for expressing

disapproval for “Vermonters.” If “Vermonters” are indicting that the

y are holier than thou (as seems fairly common), I have a tendency to want to point out that they may not be as holy as they feel. Or that the rest of us should follow them to salvation.

Supervisor: Planners rarely make the effort to really listen to the public (as opposed pretending to listen), and speak the

public language. Instead, planners use terms that must be carefully defined and have multiple definitions, like “density” and how they know better what is good for the public than does the public; things like ‘X is more dense than Y if you calculate it one way, but less dense if you calculate it another way, and we calculate it the way that gives the results we want.’ Planners don’t demonstrate they understand why the public is more concerned about short term needs like a job, an affordable day care center or a place for the kids to play soccer without fear of being abducted. They give the public the impression those should be trivial concerns, not relevant to the big picture of vibrant streets, late night activity, and locally produced food.

Dom: Largely agree. Of course, many citizens have beliefs or desires that originate from market-distorting subsidies (such as underpriced roads, parking or gasoline). So I believe that the planner must find a proper balance between actually hearing and responding to “real world” citizen needs/beliefs, and advocating tactics that they, as professionals, know to be effective in achieving community objectives. On this topic, I often like to surprise people these days by pointing out that town center living is shown in studies to be safer, more convenient, cheaper, and easier to travel in than suburbs. If these studies are accurate, and I believe they are, should I be dishonest and agree with people who state the opposite? In such a discussion, by the way, I don’t ever feel as if I would be able to persuade people that town centers are better in these ways. I believe, again, that most people will be convinced, over time, of these things as gas prices rise, roads and parking are priced, a growing number of people (particularly the wealthy) start living in town centers, the cost and profitably of town center properties rise, etc.

I’m not sure I’ve made the mistake you cite of planners trivializing needs like a job, day care or child safety. I think my (mostly) failed efforts have been to point out that town centers and traditional design results in more jobs, better/cheaper day car, and more child safety.

Now that I think about this issue, it occurs to me that I have found at least one way to be persuasive on topics such as these: Using photos in PowerPoint presentations. When I use certain images, my point can become vivid, rather undeniable, and accessible to the most un-schooled of audiences.

Supervisor: Since planners seldom connect with average citizens, they rely on appointed and elected officials to do it. They try to convince planning commissioners and city council members to sell the ideas to the public. Some public officials are believers and take on the task, or vote in opposition to public sentiment. Most don’t, and why should they? The planners aren’t their important constituents.

Dom: I’ve always liked this comment from Reubin Askew: A leader is someone who cares enough to tell the people not merely what they want to hear, but what they need to know.

I think that elected officials are (or should be) elected to be leaders. To do meaningful things, leaders know that they will make enemies – at least in the short run. Margaret Thatcher once said that consensus is the absence of leadership. One of my heroes – Enrique Penalosa (former mayor of Bogota) – was despised early on in his term. He enacted policies that aggressively inconvenienced cars in his efforts to make people, rather than cars, happy. Many wanted to throw him out of office. But eventually, his policies (which nearly all his citizens strongly opposed initially) resulted in visibly obvious quality of life and civic pride improvements. He went on to become much-loved and honored by most in Bogota.

* A city can be friendly to people or it can be friendly to cars, but it can’t be both. – Enrique Penalosa

* Over the last 30 years, we’ve been able to magnify environmental consciousness all over the world. As a result, we know a lot about the ideal environment for a happy whale or a happy mountain gorilla. We’re far less clear about what constitutes an ideal environment for a happy human being. One common measure for how clean a mountain stream is, is to look for trout. If you find the trout, the habitat is healthy. It’s the same way with children in a city. Children are a kind of indicator species. If we can build a successful city for children, we will have a successful city for all people. – Enrique Penalosa

* God made us walking animals—pedestrians. As a fish needs to swim, a bird to fly, a deer to run, we need to walk, not in order to survive, but to be happy. – Enrique Penalosa

*A premise of the new city is that we want a society to be as egalitarian as possible. For this purpose, quality-of-life distribution is more important than income distribution. [And quality of life includes] a living environment as free of motor vehicles as possible. – Enrique Penalosa

* Anything you do to make a city more friendly to cars makes it less friendly to people. – Enrique Penalosa

If I (or an American elected official) were to state anything like the above quotes, what would the reaction be?

So to answer your question above, elected officials need to acknowledge, sometimes, that public sentiment might be counterproductive (particularly in a world where misguided public subsidies and laws encourage dysfunctional behavior and ideas). Sometimes the public will undercuts public desires. Sometimes you need to make enemies. Sometimes consensus leads to ruin.

Supervisor: So, planners grumble about the uninformed public, the too-influential interest groups, and the gutless, visionless officials. Planners instead spend their time talking to each other, i.e. folks that already think the same way, or are predisposed in their direction. They avoid meaningful ongoing conversation with those who strongly disagree with them, and talk to the public in neutral settings where fixed positions can be stated and maintained. This approach guarantees slow progress toward their goals as it fosters stasis in thinking.

Dom: Agree. I’ve learned, again, that because material conditions are largely the origin of ideas and behaviors, ideas are mostly useless (unless the timing is right). By realizing this, I’ve mostly avoided banging my head against the wall. I’ve mostly avoided being frustrated by my inability to convince people of my views. I mostly like to point out, when asked, the tactics that I believe are most effective in achieving an objective. “How can we get more transit riders, Dom?” I respond by pointing out we need priced and scarce parking, relatively high gas prices/gas taxes, priced roads, compact and mixed-use development, etc. I don’t expect anyone to agree. At least not in the world we currently live in.

More so than in the past, when I “grumble,” it is about car subsidies, not uninformed people.

Supervisor: Planners come to believe they have the “right” answers. They forget there can’t be right answers or even best answers without commonly held objectives. Even then there are no right answers, there are only answers that produce different results, and often unintended or unpredictable results. So when some decision makers do follow their advice the results may not be as advertised. Oops, but believe us next time.

Dom: Yes. Which is why I often counsel against half-measures. I believe that sometimes, if a half-assed approach is taken (due, usually, to compromise), the implementation can give the concept a black eye. I’ve also sought to be better at taking a more equitable approach that can appeal to a more comprehensive set of lifestyles and choices (as long as such choices are not costly to others). Again, this is why I find the new urbanist transect concept so appealing. And the idea of “complete streets.”

And I really enjoy pointing out unintended consequences. For example, I’m currently having a discussion with a County Commissioner friend that high-mileage cars can have unintended consequences. By lowering the cost of gas, such cars can actually induce more driving…

Supervisor: Planners think those who strongly disagree are uneducated or have impure motives, because the evidence in support of the planner position is so clear and strong. They forget the lack of common objectives produces an inconsistent frame of reference to view the data.

Dom: I’ve been reading recently about the issue of “confirmation bias,” where your frame of reference leads you to tend to accept information that bolsters your perceptions and reject information that does not.

One antidote to my suffering the mistake you cite here is my reading The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Thomas Kuhn). From that book, I learned that when we devote a great deal of time and effort working with a certain paradigm, we can become immune to data that undermine the paradigm – even if the data is overwhelming. Most of us are incapable of admitting to ourselves the tragic thought that we’ve wasted so much of our lives on a failed idea. Many of us go to our graves w/o being able to change our viewpoint. It is only when the old guard dies off that the new paradigm can emerge and be accepted.

Formerly, I made the mistake of thinking that overwhelming data, evidence and logic would pretty much always carry the day and be convincing to most everyone. I now know better.

Supervisor: Planners forget, or never learn, how societal change occurs. Since cities are support structures for human society, not the reverse, planners miss the essential connection. Instead, planners see the design of cities as merely a technical issue – change these design/density characteristics, and see the happy results. The reality is that cities are the people, and the buildings and infrastructure are physical accoutrements that support the people. Fundamental change in the physical accoutrements follows fundamental change of the society. Since planners spend most of their time talking to each other and their supporters, rather than listening to the society to find unique ways to meet their needs, they ensure lack of effectiveness.

Dom: Hmmm. I’m not sure I fully understand your point here, but it reminds me of Churchill’s comment that We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us. I’m also reminded of the adage that if all we have is hammers, all our problems look like nails. With the planning profession, planners can (in theory) have an influence over infrastructure, but have little control over how people think.

I think that planners can be most effective if they can leverage the tactics that effectively influence behavior and ideas. For example, successfully influencing the size and pricing of roads, the amount and pricing of parking, the amount of gas taxes charged, the amount of impact fees charged, where buildings are placed on a piece of property, etc. Each of those tactics are effective in changing behavior and ideas.

Frankly, I’ve lost much of my previous enthusiasm for public sector planning because I find that public planners have almost no ability to influence such things. Instead, public planners are mostly in the role of implementing land development regulations that, in a great many ways, undercut sustainable, Smart Growth designs.

intersections oversized and therefore nearly impossible to walk or bike; too little mixing of housing with offices or shops; too much free parking; too little traffic calming; too little road tolling; gas and gas taxes (and other motor vehicle taxes/fees) too low in price or absent; too many one-way streets; excessive parking requirements; over-concern about traffic congestion; failure to adopt an “Idaho Law;” silo-ing transportation and land use so that each is considered without the other; widespread lack of knowledge about (or outright opposition to) effective tools to shift motorists from cars to non-motorized travel; signal lights synchronized for car speeds rather than bus/bike speeds; failure to slow the growth in over-sized service vehicles; widespread belief in the myth that freer-flowing traffic reduces emissions and fuel consumption; over-emphasis on mobility rather than accessibility; no trend analysis of important measures such as quantity of parking or VMT per capita; extremely inflated estimates of bicycling levels that are not even close to reality; over-emphasis on stopping growth or minimizing density as a way to reduce car trips (such efforts actually increase per capita car trips); too much effort directed at creating more open space within the city (the city has way too much open space in part because so much of it is for cars); too much use of slip lanes and turn lanes in places they do not belong; widespread belief in the myth that car travel is win-win (it is actually zero-sum); failure to use raised medians in several locations; making bicycling impractical on hostile streets (due to extreme danger); and over-use of double-yellow center lines.

intersections oversized and therefore nearly impossible to walk or bike; too little mixing of housing with offices or shops; too much free parking; too little traffic calming; too little road tolling; gas and gas taxes (and other motor vehicle taxes/fees) too low in price or absent; too many one-way streets; excessive parking requirements; over-concern about traffic congestion; failure to adopt an “Idaho Law;” silo-ing transportation and land use so that each is considered without the other; widespread lack of knowledge about (or outright opposition to) effective tools to shift motorists from cars to non-motorized travel; signal lights synchronized for car speeds rather than bus/bike speeds; failure to slow the growth in over-sized service vehicles; widespread belief in the myth that freer-flowing traffic reduces emissions and fuel consumption; over-emphasis on mobility rather than accessibility; no trend analysis of important measures such as quantity of parking or VMT per capita; extremely inflated estimates of bicycling levels that are not even close to reality; over-emphasis on stopping growth or minimizing density as a way to reduce car trips (such efforts actually increase per capita car trips); too much effort directed at creating more open space within the city (the city has way too much open space in part because so much of it is for cars); too much use of slip lanes and turn lanes in places they do not belong; widespread belief in the myth that car travel is win-win (it is actually zero-sum); failure to use raised medians in several locations; making bicycling impractical on hostile streets (due to extreme danger); and over-use of double-yellow center lines.

trivial by comparison (such as parks, water, schools, etc.). “Sufficient” roads and parking is equated with maintaining quality of life.

trivial by comparison (such as parks, water, schools, etc.). “Sufficient” roads and parking is equated with maintaining quality of life.