By Dom Nozzi

July 15, 2015

On July 14, 2015, I posted an article that discounted many of the alleged benefits of bicycle helmets on Facebook. The article was published on June 26, 2015 by Lindsey Wallace in The Spokesman Review. http://www.spokesman.com/blogs/transportation/2015/jun/26/why-im-done-wearing-helmet/

The claims made in the article largely track what I have seen academically, professionally, and in my own personal life as a bicycle commuter over the years.

Immediately, Facebook friends inundated my Facebook wall with patronizing, emotionally charged, disparaging, outraged comments that attacked and questioned the article, and were puzzled (to put it politely) by my decision to promote such an obviously flawed report.

What struck me very quickly was the combination of a lack of credentials (credibility) and the UTTER CERTAINTLY of nearly all of those who posted such vicious, abusive comments. It was as if I was promoting a study that claimed that smoking was good for your health or that women should be subservient to their husbands.

As I noted above, many of the points made in the report tracked what I had seen over the years with bicycle research, design and personal experience. Yet people with no academic, professional, or personal background (as bicycle commuters) became apoplectic — red-faced in anger — in their Facebook attacks. One called the report the “stupidest” thing he had ever seen (another friend suggested me or the author were suicidally moronic and supporters of this crazy report would lead to our being weeded out of the gene pool in a “Darwinian” sense). How, I asked myself, were people who had no academic or professional background in bicycling able to trash a report within a few seconds of seeing it, and having therefore not pointed to studies that counter claims made in the report?

Does this avalanche of hostility help explain why so few strategies are effectively employed in the US to grow the number of bicycle commuters?

Who am I – Dom Nozzi – to support the views expressed in the report, and to question the credibility of Facebook friends who attacked the article as well as me?

My credentials, which are almost entirely absent for those friends doing the attacking:

- Master’s Thesis on the topic of bicycle transportation I completed to obtain a Master of Science degree in town planning from Florida State University. This required years of relatively exhaustive academic research regarding bicycling theory and practice at a national and worldwide level.

- Approximately 45 years of one to four utilitarian (work, shopping, meetings, etc.) bicycle trips on a daily basis (ie, 365 days per year or about 16,000 to 66,000 bicycle trips) – mostly within a low-speed town center.

- Twenty years as a professional town and transportation planner for a university town in Florida, where I prepared bicycle-related land development regulations, and long-range citywide bicycle transportation (and greenway path) plans. This required several years of professional research regarding bicycle transportation design and promotion.

- A year of membership on the Bike/Walk Virginia Board of Directors (an advocacy group for bicycling and walking in Virginia).

- Reading a vast number of books, articles, reports, and studies regarding all aspects of bicycling.

- Writing a vast number of essays regarding many aspects of bicycling.

- Publishing two books that devoted many pages to many aspects of bicycling.

- Bicycle commuting as a resident for several years in bicycle-friendly towns in the US (Flagstaff AZ, Gainesville FL, and Boulder CO).

- Bicycling for several days in some of the world’s leading bicycling cities: Amsterdam, Malmo and Copenhagen (I have to wonder how many of my attacking Facebook friends know that only a very small number of Europeans – where bicycling is

enormously more common than in the US – wear bicycle helmets? How many know that despite this, the per capita rate of bicyclist head injuries is much lower in Europe than in the US?).

How many of my friends know that the mandatory bike helmet laws that they mostly or entirely support have resulted in such a large decrease in bicycling that overall public health and safety have declined in those places?

How many of my friends know that as I understand it from a few of my colleagues who do/did this work professionally, most professional bicycle planners and engineers employed by cities and counties in the US agree with my position on bike helmets, but are unable to openly state such a position due to the extremely hostile reaction they would get from supervisors, elected officials, and residents? (the abusive, patronizing, dismissive comments from many of my Facebook friends are an example of what one faces when expressing such an un-PC position)

How many of my friends know that much research now shows that “safety in numbers” (SiN) is, by far, the most effective technique for improving bicyclist safety? (and that for better bicycling safety, American needs to find effective ways to grow the number of cyclists).

How many of my friends know that one of leading reasons cited for not being a bicycle commuter is the perceived danger of bicycling? (bike helmets perpetuate this problem by sending a very visible, strong message that bicycling is DANGEROUS!)

How many of my friends know that bike helmets are a form of “blaming the victim” ? (ie, bike crashes are the fault of cyclists, not reckless motorists)

How many of my friends know that research has found that motorists dangerously give less clearance (drive closer) to cyclists who wear helmets?

How many of my friends know that bike helmets do nothing to reduce the likelihood of a cyclist getting in a crash? (some studies have found that helmets INCREASE the likelihood a bicyclist will crash)

How many of my friends know that I wear a helmet for two out of the three forms of bicycling I engage in? (single-track mountain bicycling and long-distance suburban and rural cycling)

How many of my friends know that I am NOT suggesting that NO ONE ever wear a helmet. If a cyclist wants to wear a helmet (and the inconvenience of doing so will not discourage them from regular bicycling), please be my guest and wear one! Many scoff at my claim that wearing a helmet is inconvenient, and therefore insist that cyclists should find it easy to wear one (and even be REQUIRED to wear one). I wonder how many of my motorist friends happily agree to wear a helmet each time they drive a car…

How many of my friends know that a very large number of Americans – particularly women – are concerned about their appearance (particularly their hair), and that helmets tend to make a person look “dorky” and have “helmet hair” when the helmet is removed? Do we know how many are discouraged from bicycling due to concerns about such fashion?

How many of my friends know that an important way to promote more bicycling is to “normalize” it? (that is, to create the impression – by wearing street clothes rather than lycra and a helmet – that bicycling is something that normal — and even hip — people do). Personally, I was astonished by how “normal,” “safe,” and “hip” I felt when I was bicycling alongside THOUSANDS of fellow bicyclists in Amsterdam – All Americans need to experience that feeling.

How many of my friends know that there is very little, if any, evidence that motorists pay higher insurance premiums because – allegedly — bicyclists who don’t wear helmets have astronomical head injury hospital costs? (for the record, the only bike crash resulting in a medically costly head injury in my entire life was one where I was wearing a helmet – I might have been killed that day had I not worn a helmet on that single-track dirt trail)

How many of my friends know that the chance of a head injury for a bicyclist riding in a low-speed town center environment is exceedingly low – much lower than the risks faced by motorists (who do not wear helmets)?

How many of my friends know how many costs and inconveniences and difficulties American bicyclists face in a nation that has spent over a century spending trillions to pamper cars (and encourage the high-speed movement of cars)? How many realize that a bicycle helmet adds yet ANOTHER inconvenience to the already terribly inconvenienced bicycle commuter?

How many of my friends know that bicyclists pay far more than their fair share of road costs, and that motorists pay far less than their fair share? How many know that American motorists are the most heavily subsidized group on earth? How many know that because nearly all motorist parking is provided free to the motorist that the cost of groceries, hair cuts, medical expenses, housing, taxes, etc., are much higher for all of us – INCLUDING, UNFAIRLY, BICYCLISTS? As Donald Shoup points out in The High Cost of Free Parking, when nearly all motorist parking is not paid directly by the parking motorist, that cost is transferred to all of us in the form of higher cost of living.

How many of my friends know that studies show a person – on average – will live longer, healthier lives riding a bicycle (even without a helmet) than a person who drives a car?

How many of my friends realize how inconvenient it is to wear a helmet for the 10 to 30 trips per week that a bicycle commuter takes?

How many of my friends where helmets when they drive a car? I suspect none, even though driving is much more likely to result in head injuries than bicycling.

How many of those attacking me and the bike helmet report — with complete certainty, mind you — have ANY of the above credentials or background? Or anything resembling credentials regarding bicycling research, advocacy, professional work, or personal bicycle travel behavior?

Why is it so brutally obvious for non-bicyclists to know with complete accuracy what makes sense regarding bicycling safety, promotion, and advocacy?

Given the above, I think I have every right to be insulted by alleged bicycling “experts” who attack me and the report as “stupid.”

But I’m not so much insulted as FRUSTRATED, as the attacks exemplify why such a tiny, tiny percentage of Americans (less than one percent?) are bicycle commuters. After all, how is it possible for American communities to substantially increase the number of bicycle commuters when nearly all of us are both utterly uninformed in bicycling and yet utterly certain we are bicycling experts?

I am convinced that it is, indeed, quite possible to build sidewalks that are too wide.

I am convinced that it is, indeed, quite possible to build sidewalks that are too wide.

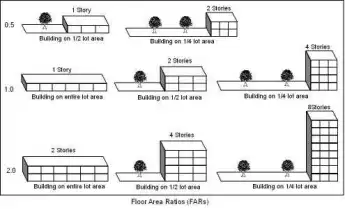

An FAR of 2.0 means the developer is allowed to build the equivalent of a two-story building over her entire lot, or a 4-story over half the lot.

An FAR of 2.0 means the developer is allowed to build the equivalent of a two-story building over her entire lot, or a 4-story over half the lot. America, as you can imagine, most of our commercial areas have developed FARs of about 0.1 (with most space taken up by surface parking).

America, as you can imagine, most of our commercial areas have developed FARs of about 0.1 (with most space taken up by surface parking). University. Instead, they’ll need to hop in their cars to cross those stroads as they now do at the Gainesville Mall and Butler Plaza — which is an outright attack against City plans in recent years to make the Westgate area more walkable).

University. Instead, they’ll need to hop in their cars to cross those stroads as they now do at the Gainesville Mall and Butler Plaza — which is an outright attack against City plans in recent years to make the Westgate area more walkable). travel by walking, bicycling or transit less safe, desirable, or feasible. Coupled with the excessively low densities that NIMBYs demand, and the enormous amount of space cars consume (17 times more than a person in a chair), Boulder’s roads and parking lots quickly and ironically become rapidly congested. This congestion, caused at least partly by NIMBYism, motivates NIMBYs to scream for even MORE opposition to development and compact design.

travel by walking, bicycling or transit less safe, desirable, or feasible. Coupled with the excessively low densities that NIMBYs demand, and the enormous amount of space cars consume (17 times more than a person in a chair), Boulder’s roads and parking lots quickly and ironically become rapidly congested. This congestion, caused at least partly by NIMBYism, motivates NIMBYs to scream for even MORE opposition to development and compact design. building height even in the most urbanized areas of Boulder is now a crazy low 35 feet in the town center (Boulderado is 55 ft). In addition, the building design regulations say almost nothing about creating similar buildings going forward.

building height even in the most urbanized areas of Boulder is now a crazy low 35 feet in the town center (Boulderado is 55 ft). In addition, the building design regulations say almost nothing about creating similar buildings going forward.

building design over modernist design. One way to measure this (besides the many opinion polls) is to realize that it may not be possible to identify a single city skyline in the world that is broadly loved AND that consists primarily of modernist building styles. Consider this image…

building design over modernist design. One way to measure this (besides the many opinion polls) is to realize that it may not be possible to identify a single city skyline in the world that is broadly loved AND that consists primarily of modernist building styles. Consider this image… congestion!). But mostly because most residents in Boulder live in neighborhoods that are very low in density and consist of “single-use” land use patterns. Only housing is found in the neighborhoods. Jobs, services, shopping, culture, and recreation tend to be several miles away, and often reachable only on high-speed, dangerous roads. This state of affairs means that for nearly all Boulder residents, it is impractical to travel by any means other than car. Given that, most all Boulder residents see travel lane removal as severely restricting their ability to travel.

congestion!). But mostly because most residents in Boulder live in neighborhoods that are very low in density and consist of “single-use” land use patterns. Only housing is found in the neighborhoods. Jobs, services, shopping, culture, and recreation tend to be several miles away, and often reachable only on high-speed, dangerous roads. This state of affairs means that for nearly all Boulder residents, it is impractical to travel by any means other than car. Given that, most all Boulder residents see travel lane removal as severely restricting their ability to travel. traffic congestion. What we have now quite conclusively learned is that widening a street will not durably reduce congestion, and the new car trips induced by the widening create a vast array of new problems.

traffic congestion. What we have now quite conclusively learned is that widening a street will not durably reduce congestion, and the new car trips induced by the widening create a vast array of new problems. intent of my recommendations for the project is to see that the design of the project promotes walkability, sociability, neighborhood safety and security, travel choice (particularly for seniors and children), relatively low noise levels, timeless styles and design, and low per capita car trip generation.

intent of my recommendations for the project is to see that the design of the project promotes walkability, sociability, neighborhood safety and security, travel choice (particularly for seniors and children), relatively low noise levels, timeless styles and design, and low per capita car trip generation.