A Facebook Conversation between Dom Nozzi and a friend

December 18, 2016

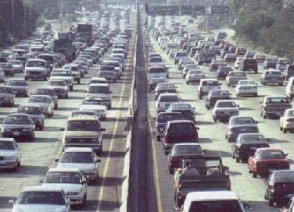

In December of 2016, a Facebook friend of mine responded to an illustration I posted showing the ENORMOUS amount of space that cars consume.

Friend: Then what’s the answer for Boulder, Dom?. Can [the Boulder Transportation Advisory Board (TAB) you sit on] or the City do much more to encourage bus and bike usage, especially in winter?

Dom Nozzi: The politics and values I have observed in Boulder spell very bad news for Boulder’s future. I’ve been surprised by how uninformed the Boulder population is on transportation (it is a national problem, but a surprise to me that this is also true in allegedly informed Boulder).

A large number in Boulder have opted for the strategically ruinous strategy of equating free flowing traffic with quality of life. Traffic congestion is viewed (like nearly everywhere else in the world) as a terrible problem that must be reduced. Given the huge amount of space that cars consume, this common desire inevitably means that Boulder is over-widening its streets and intersections, and has spent decades trying to prevent – or at least minimize — development densities (it is wrongly believed in Boulder that this would reduce the crowding of roads and parking lots).

The results include a lot of suburban sprawl (in the form of wanna-be-Boulder towns in areas surrounding Boulder), very unsafe roads and intersections (because they are over-sized), a city that is too dispersed to make walking practical, and a city that contains oversized car habitats (such as huge, numerous parking lots) that degrade quality of life.

This state of affairs has meant that Boulder has been unable to meaningfully increase the number of people who walk, bicycle or use transit for several years.

It will be a long process to change this reality, but Boulder needs to see new politically influential pro-city activist groups arise (such as Better Boulder) to reverse this downward spiral. A better future centers on reducing the three “S” factors: Reduce Space allocated to cars, reduce Speeds cars can travel, and reduce Subsidies that motorists enjoy. Doing so will consequently deliver more compact, mixed development, and better quality of life, a better economic situation, and a lot more safety and choice of both lifestyle and forms of travel.

Until Boulder moves away from its long-term strategy of pampering cars and thinking doing so can be a win-win strategy with bicycling, walking, and transit, city design will continue to be overly car-friendly. Roads and intersections too big, car speeds too high, and motorist subsidies too inequitable.

Can TAB do anything to encourage less car dependence? Sure, if we start adopting the above tactics by ending our counterproductive efforts to make cars happy. I have a very long list of needed transportation reforms for Boulder that seem highly unlikely to be adopted for a long time. I am very surprised by how behind-the-times Boulder is regarding transportation, despite the conventional wisdom. There are very few short-term tactics we can deploy.

Reforming parking would be a good start. I continue to strongly support road travel lane repurposing. For decades, the City has mostly taken the easy path of spending money to address transportation issues. But again, it is about taking away size, speed and subsidies from motorists. It is not about spending money on bike lanes, transit, and sidewalks. In the winter, transportation choice is highly unlikely without compact development. Boulder, in short, has its work cut out for it.

Facebook friend: Replace “motorists” with “citizens”. Do the citizens of Boulder support these initiatives? I sometimes get the sense that some on TAB believe they have the correct answers and don’t really care what the people of Boulder actually think, hence the right sizing controversy on Folsom. Public outreach and forming a collective vision for the future of our city is key to any kind of reform that impacts people’s preferred mode of transportation.

Dom Nozzi: Very few motorists (using “citizens” implies that we are all motorists and non-motorists do not matter) support these ideas in Boulder or elsewhere in the US. This is largely because of a century of huge motorist subsidies and the fact that over-providing for motoring is a self-perpetuating downward spiral. That is, the bigger we make roads  and intersections and parking (to keep motorists happy), the more difficult and unsafe travel becomes for non-motorists (which continuously recruits more motorists, thereby adding to the downward spiral).

and intersections and parking (to keep motorists happy), the more difficult and unsafe travel becomes for non-motorists (which continuously recruits more motorists, thereby adding to the downward spiral).

Support for these ideas tends to emerge only when motoring pays its own way and does not degrade the human habitat (ie, the gas tax is substantially increased, road tolls and parking charges are instituted, and roads are kept at modest widths to keep car speeds relatively low).

A great many useful transportation tactics are highly counter-intuitive (the Folsom right-sizing road diet project is a good example). In Boulder and throughout the nation, motorists predictably fight aggressively against such leveling of the playing field and protecting quality of life because they are living a life where travel by car is obligatory (due largely to car-only, oversized road design, as well as the large distance to destinations). They see little choice other than to keep spending trillions of public dollars to widen roads and intersections and provide more “free” parking.

Because doing such things is unsustainable, destructive, and detrimental to community safety, we therefore become our own worst enemy.

My comments above illustrate an enormous dilemma that spell a grim, difficult, painful future. There are very few (if any) painless, easy, quick, popular, effective, win-win tactics to improve our transportation system, given our century-long track record. “Public outreach” is almost entirely ineffective in a world that is so heavily tilted toward enabling easy, low-cost motoring. What good would it do, for example, to “public outreach” to motorists who live several miles from their destinations to suggest they should consider riding a bike or walking on a dangerous, car-only road for 7 miles? Only when the playing field is more level and community design more conducive will such outreach be useful.

TAB members are appointed by Council at least in part to provide advice on improving transportation based on our knowledge of transportation. This knowledge comes from our academic and professional background, our experiences of spending years getting around in Boulder, reading adopted community plans, and our listening to others in the community.

Sometimes the advice from TAB (or from Planning Board or Council) is not popular. But this is the nature of dealing with a transportation world I describe above. If “most popular” was the only means of deciding what to do, we would not need Council or advisory boards. We would simply have a computer measure community opinion on various measures. Instead, we have a representative democracy because such a direct democracy approach is unworkable and undesirable (particularly for complex, counter-intuitive issues). And because of the dilemmas I cite above, strong leadership in transportation is extremely important. I have always liked the following observations on leadership:

A leader is someone who cares enough to tell the people not merely what they want to hear, but what they need to know. — Reubin Askew

Margaret Thatcher once said that consensus is the absence of leadership.

To achieve excellence should be a struggle. – Charleston Mayor Joseph Riley

To avoid criticism, do nothing, say nothing, be nothing. — Elbert Hubbard

One of my heroes – Enrique Penalosa (former mayor of Bogota) – was despised early on in his term — largely because he enacted policies that aggressively inconvenienced cars in his efforts to make people, rather than cars, happy. Many wanted to throw him out of office. But eventually, his policies (which nearly all his citizens strongly opposed initially) resulted in visibly obvious quality of life and civic pride improvements. He went on to become much-loved and honored by most in Bogota.

Let us not forget that back in the day, the majority opinion was to oppose granting equal rights to women, blacks, non-Christians, or gay/lesbian people. Nearly all of us believed the earth was flat. That smoking and DDT were okay.

By the way, it may comfort you to know that my views — because they are so counter to the conventional wisdom in Boulder –tend to be ignored by other TAB members, city staff and by Council. On most all “tough” votes, I am almost always on the losing end of 4-1 TAB votes (would transportation be “better” in Boulder, in your view, if those TAB votes were 5-0?).

For a century and up to the present day, Boulder citizens, elected and appointed officials, and staff have been nearly unanimous in thinking that happy motoring was and is a good idea. In my view, that has been a tragic mistake. Boulder can do much better if it discarded that discredited (yet conventional) view.

Overall, like standard cars, autonomous cars are extremely toxic to cities. To be healthy, cities require slow speeds (which promote the agglomeration economies that cities require). Higher speeds induce more low-density dispersal, which destroys city health and the essential need for social capital. Cars isolate us, yet our genes and our cities need interaction.

Overall, like standard cars, autonomous cars are extremely toxic to cities. To be healthy, cities require slow speeds (which promote the agglomeration economies that cities require). Higher speeds induce more low-density dispersal, which destroys city health and the essential need for social capital. Cars isolate us, yet our genes and our cities need interaction. time is significantly slowed. Boulder would benefit from having Burden conduct a traffic calming audit with the Boulder fire department, and demonstrate designs that slow cars without slowing fire trucks.

time is significantly slowed. Boulder would benefit from having Burden conduct a traffic calming audit with the Boulder fire department, and demonstrate designs that slow cars without slowing fire trucks. safety efforts. This morning, I looked for a chart showing the trend in the number of annual deaths on US roadways. I have included a few charts from Wikipedia in this blog. “Annual Traffic Deaths” shows the crazy high number of annual deaths.

safety efforts. This morning, I looked for a chart showing the trend in the number of annual deaths on US roadways. I have included a few charts from Wikipedia in this blog. “Annual Traffic Deaths” shows the crazy high number of annual deaths. inside them) safer with such things as seat belts, air bags, and aggressive efforts against drunk driving – not to mention our removing a lot of trees and other “hazards” from near the side of roads.

inside them) safer with such things as seat belts, air bags, and aggressive efforts against drunk driving – not to mention our removing a lot of trees and other “hazards” from near the side of roads.

LOT more cars. What an irony, since NIMBYs HATE more crowded roads and parking lots.

LOT more cars. What an irony, since NIMBYs HATE more crowded roads and parking lots.