By Dom Nozzi

[Updated Jan 2009]

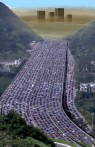

Car Dependence. The percentage of trips made by the population of a community that are made by car, as opposed to bicycle, transit, or walking, is perhaps the most important quality-of-life indicator available. This is evidenced by the fact that the majority of the problems addressed by urban planners in American communities are either directly or indirectly related to excessive auto dependence.

Think about how often we see a neighborhood group objecting to a proposed nearby development due to fear of the noise, traffic congestion, visual blight, and safety problems associated with the many cars expected to be associated with the development. Small churches and grocery stores, which were formerly compatible with neighborhoods, are now largely feared by neighborhoods due to a concern for the heavy traffic volume produced by today’s over-sized churches and supermarkets.

Communities across America are seeing enormous increases in the number of per capita car trips being made. Little wonder that so many public meetings have come to attract so many angry neighborhood groups. After all, traffic volume data throughout the nation shows that a great many communities are clearly losing its struggle to remain livable in the face of these enormous increases in auto use and dependence.

Negative Impacts of Auto Dependence. The threat that excessive auto dependence represents to a community are now well known. Autos and their infrastructure are the leading cause of air and water pollution (about 85 percent, by weight, of all air pollution) in many urban areas. They are the leading cause of serious accidents, wildlife mortality, habitat fragmentation, neighborhood disruption, and visual blight. They are the leading source of noise pollution (about 85 percent of all noise). They result in the creation of massive structures scaled for vehicles instead of people. They facilitate sprawl development. They destroy small businesses and downtowns by encouraging the development of huge shopping malls. They reduce neighborliness by “cocooning” people when they travel. And they reduce the viability of transit, bicycling and walking.

Because they are so expensive to purchase and operate, cars are overburdening family budgets. (The average vehicle now costs about $7,000 per year as of 2008, which means families are now spending more on transportation than on food.) This burden affects both rich and poor, since, as was shown by Newman and Kenworthy (1989), there is little correlation between income and car ownership. And the huge costs associated with maintaining and expanding such structures as roads and parking lots is bankrupting federal, state, and local governments—not to mention small businesses.

The magnitude of these costs is astounding. Researchers at the University of California–Davis estimated about 20 years ago that vehicle-produced air pollution results in up to $200 billion per year in economic costs. State and federal governments at that time spent $71 billion per year for road construction and maintenance. Businesses and taxpayers 20 years ago were spending another $175 billion per year for additional road maintenance, police, fire, ambulance service, and parking. Back then, the military activity needed to safeguard oil  supplies costs us $50 billion per year. Productivity declines due to traffic jams cost up to $140 billion per year at that time. And the bill for accident-related property damage, medical expenses, court costs, and emergency services at that time was $350 billion per year.

supplies costs us $50 billion per year. Productivity declines due to traffic jams cost up to $140 billion per year at that time. And the bill for accident-related property damage, medical expenses, court costs, and emergency services at that time was $350 billion per year.

It goes without saying that the costs cited above are much larger today, 20 years later.

As for environmental sustainability, in 1980 vehicles consumed 56 percent of the petroleum, 72 percent of the rubber, 30 percent of the zinc, and about 20 percent of the aluminum used in the U.S. About 80 percent of the energy in the gas consumed by cars is wasted. (Miller, 1979).

Land Use Patterns and Vested Interests

How did it come about that we are now so irreversibly committed to a draconian love affair with the car? How did we get ourselves into this (traffic) jam?

Conspiracy theorists point to efforts by major auto makers to scuttle bus and trolley systems throughout the U.S. several decades ago. Many suggest that the elegance and convenience provided by the car are irresistible to luxury-minded Americans, or that a feeling of powerlessness leads people to seek prestige and significance through owning an impressive vehicle. Others argue that cars are a necessary “suit of armor” to protect citizens from muggers and rapists.

While some of these factors may have played a role in our attraction to cars, the most compelling evidence points to land use patterns, vested interest, and low cost as the primary causes of auto dependence.

Land Use Patterns. Remote, low-density residential development (sometimes referred to as “suburban sprawl”) places many people at such a great distance from schools, shopping areas, parks, and work sites that the car has become the only realistic means of travel. According to a worldwide study of cities by Newman and Kenworthy (1989), the threshold density for making mass transit, biking, and walking viable appears to be approximately 12 persons per acre (about 8 to 9 dwelling units per acre). Below this density, auto dependence and gas consumption increase exponentially. Bus service and walking declines, and household auto ownership increases.

In fact, the study found that gasoline use is an accurate barometer of the amount of auto dependence being experienced by a community. Gasoline consumption has risen substantially in nearly all communities over the past 20-30 years.

To combat the low-density trend that leads to auto dependence, several communities are beginning to encourage higher density development near transit stops, and curtailing any further growth in outlying urban fringe areas (a strategy Newman and Kenworthy felt was essential).

Another major land use problem promoting excessive auto use is the lack of “mixed-use” downtowns. The downtowns of U.S. cities generally have a very high proportion of jobs and very few residents, whereas in Europe there is a much better balance of jobs and residences. Newman and Kenworthy found that concentrating jobs downtown—in and of itself—has little effect on reducing auto dependence, whereas a balanced mix of jobs and housing downtown results in much less auto use. Some cities now require developers to provide a certain amount of downtown housing in conjunction with downtown office development.

Nevertheless, most Americans seem to prefer low-density suburbs with plenty of private open space, and look with disdain upon “city living.” The trade-off is that such land use patterns typically lead to an increase in the amount of land devoted to residential and commercial development, less public open space, higher taxes, higher gasoline consumption, and less ability to reduce air and water pollution (due to high levels of auto dependence).

Increasingly, however, higher density mixed-use urban developments are becoming attractive due to the easy access to urban facilities and the more interesting, convivial, and active community provided by such developments. The city becomes safer and more “defensible” (due to an increase in citizen-watching and citizen caring) with much less space abandoned at night to criminals and gangs (Newman and Kenworthy, 1989).

Vested Interest. Most believe that the land use plan guides the transportation planner. However, as Newman and Kenworthy point out, “one of the major reasons why freeways around the world have failed to cope with demand is that transport infrastructure has a profound feedback effect on land use, encouraging and promoting new development wherever the best facilities are provided (or are planned)…momentum develops which is very hard to stop. The obvious response to the failure of freeways to cope with traffic congestion is to suggest that still further roads are urgently needed. The new roads are then justified again on technical grounds in terms of time, fuel and other perceived savings to the community from eliminating the congestion. This sets in motion a vicious circle…of congestion, road building, sprawl, congestion and more road building. This is not only favorable to the vested interests of the road lobby and land developers but it also builds large and powerful government road bureaucracies whose professional actors see their future as contingent upon being able to justify large sums of money for road building…In this way road authorities can become de facto planning agencies directly shaping land use…” The immensity of these organizations is now such that approximately one out of every five dollars spent in the U.S. is related directly or indirectly to the auto industry (an industry that employs over 15 percent of the total U.S. workforce).

The individual also has a powerful vested interest to put mileage on the car. The huge purchase price and insurance premiums necessary for car ownership make it irrational for someone to let such an investment just sit in the driveway.

Low Cost. The cost of driving includes fuel cost, congestion and time delay cost, taxes, and parking fees. Because driving a car is heavily subsidized by government and businesses, these costs are extremely low. Gas is cheap, there is too much free parking, and roads are not very congested. The significant social and environmental costs are therefore borne by society at large, rather than the motorist and the auto-making industry.

Our relentless battle to reduce traffic congestion is one example of how costs are minimized to the detriment of a higher quality of life. Conventional wisdom states that free-flowing traffic (which traffic engineers seek to encourage through computerized traffic signals and  widened roads) reduces gasoline consumption and air pollution. However, Newman and Kenworthy found that the reverse is true. Reduced congestion results in reduced traffic delays experienced by the motorist (which translates into a reduced cost to the motorist), and increased incentives for the development of remote, low-density residential sprawl development. This results in an increase in auto trips and an increase in the length of such trips—an increase which far exceeds the gas consumption reductions caused by reduced congestion.

widened roads) reduces gasoline consumption and air pollution. However, Newman and Kenworthy found that the reverse is true. Reduced congestion results in reduced traffic delays experienced by the motorist (which translates into a reduced cost to the motorist), and increased incentives for the development of remote, low-density residential sprawl development. This results in an increase in auto trips and an increase in the length of such trips—an increase which far exceeds the gas consumption reductions caused by reduced congestion.

Similarly, widening roads, increasing central city parking, and increasing average vehicle speed reduces costs that motorists would otherwise experience had it not been for such government subsidies. The results of these forms of motorist subsidy are higher per capita vehicle ownership, higher levels of driving per capita, higher levels of auto commuters, lower per capita use of transit, and lower per capita walking and biking. The most auto-dependent cities have 2 1/2 times more downtown parking per 1000 jobs than less dependent cities. Newman and Kenworthy call for no more than 200 parking spaces per 1000 downtown jobs.

Supply and Demand. It seems, therefore, that we should be less concerned about eliminating “shortages” of traffic lanes and parking lots. As was pointed out above, reducing congestion may do more harm than good. As for shortages, U.S. cities provide about three to four times as much road per capita as in European cities, and 80 percent more central city parking, according to Newman and Kenworthy.

Not only do these researchers find a relative excess of space for cars, but they also argue that traffic congestion has several positive effects on a community: It reduces the number of vehicle miles traveled and therefore the amount of gasoline consumed. It also increases the viability of transit. As early as the 1960s, European cities (and more recently, certain U.S. and Canadian cities), started to acknowledge that attacking congestion was an exercise in futility. It was found that building and widening roads “was destroying cities and not helping the congestion situation either.” In fact, by increasing road capacity, we are merely putting off the day of reckoning when a more rational, less auto-dependent society is forced upon us by the high cost of such dependence.

Robert Best, writing in the July 1992 issue of Land Lines (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy) also looks with disdain upon the traditional “supply-side” approach of transportation policy-makers. By investing heavily in new highways to accommodate traffic increases, Best points out that motorists are able to travel at will—with little or no penalties (in terms of congestion delays or travel fees) to constrain their driving. Partly as a result, congestion levels have skyrocketed.

Increasing the supply by building and widening roads is akin to solving energy problems by increasing the rate of off-shore oil drilling. In other words, increasing the amount of pavement is a short-term “quick fix” which encourages further dependence on socially and environmentally destructive behavior.

Fortunately, there is a rational alternative. Today, more progressive transportation planners are using “demand management” strategies to solve traffic problems. Instead of pouring millions of dollars into neighborhood-destroying road widenings, these planners strive to reduce the amount of driving—which is akin to the low-cost and environmentally sustainable strategy of using conservation as a solution to energy shortages. Demand management is now being employed in cities such as Boston and Los Angeles, where massive supply-side efforts in the past have led to spectacular and costly failures to eliminate traffic problems.

What types of demand management strategies have been most effective? Some communities simply use traffic congestion to encourage motorists to adopt alternative commuting behavior. Others are providing financial rewards for employees who car-pool or ride a bus. Special traffic lanes (usually called “high occupancy vehicle lanes”) have been designated in many cities for the sole use of buses or car-poolers. Still others charge a fee to motorists based on the frequency of driving—particularly for driving during congested times of day. Of course, the compact, mixed-use, higher-density land use strategies described earlier represent longer-term approaches to “managing demand.”

Traffic “Taming.” Lennard and Lennard (1987) note that “livable” cities are characterized by their efforts to reduce traffic impacts in order to improve social interaction, create a sense of place, reduce pollution and noise, create vibrant and festive pedestrian areas, and increase citizen comfort in public places. Planners in Europe, and increasingly in the U.S., are using traffic “taming” strategies such as: (1) designs to reduce vehicle speeds and drive-through traffic; (2) re-designing streets to allow for more on-street parking, landscaping, and pedestrian activity; (3) mixing land uses so that homes are close enough to shops, schools, and work sites to make cars less necessary; and (4) reducing the amount and increasing the cost of auto parking. Traffic-taming designers give highest priority to pedestrians, then bicycles, then transit, and then autos—which is the reverse of the traditional approach.

Newman and Kenworthy concur. Their study found that cities most effective in minimizing gasoline consumption and reducing the proportion of trips made by car typically have the most attractive, human-oriented and human-scaled city centers. These cities place a low priority on providing auto parking or other auto-pampering facilities.

As Andres Duany has pointed out, we have spent the past several decades designing our communities to make cars happy. Perhaps it is time to re-order our priorities. If we are truly interested in creating a more livable county, perhaps it is time to focus on making people happy.

________________________________________________

Visit my urban design website read more about what I have to say on those topics. You can also schedule me to give a speech in your community about transportation and congestion, land use development and sprawl, and improving quality of life.

Visit: www.walkablestreets.wordpress.com

Or email me at: dom[AT]walkablestreets.com

My memoir can be purchased here: Paperback = http://goo.gl/9S2Uab Hardcover = http://goo.gl/S5ldyF

My memoir can be purchased here: Paperback = http://goo.gl/9S2Uab Hardcover = http://goo.gl/S5ldyF

My book, The Car is the Enemy of the City (WalkableStreets, 2010), can be purchased here: http://www.lulu.com/product/paperback/the-car-is-the-enemy-of-the-city/10905607

My book, Road to Ruin, can be purchased here:

http://www.amazon.com/Road-Ruin-Introduction-Sprawl-Cure/dp/0275981290

My Adventures blog

http://domnozziadventures.wordpress.com/

Run for Your Life! Dom’s Dangerous Opinions blog

http://domdangerous.wordpress.com/

My Town & Transportation Planning website

http://walkablestreets.wordpress.com/

My Plan B blog

My Facebook profile

http://www.facebook.com/dom.nozzi

My YouTube video library

http://www.youtube.com/user/dnozzi

My Picasa Photo library

https://picasaweb.google.com/105049746337657914534

My Author spotlight

http://www.lulu.com/spotlight/domatwalkablestreetsdotcom