By Dom Nozzi

Someone read one of my blogs about my ratings for the best cities in the world. He then asked me the following: “How would you rate Vancouver? Would it potentially make it on your best-ever list in the future? And what do you think is the reason why it seems to get so much amazing press? From a cursory Google Images search, the downtown looks to me like a whole lot of nondescript glass towers.”

I responded by noting that I’ve long been intrigued by Vancouver, as the city is often ranked quite high as a quality city, which led me to be eager to visit to see for myself.

When I visited, I was disappointed.

The city has a lot of rather tall, intimidating glass and modernist towers. I did not find much at all in the way of charming walkability or human scale.

It was easy to see that as noted by reports, the city has quite a bit of town center housing, which surely must be good news for town center retailers (and, perhaps, a good amount of town center walking).

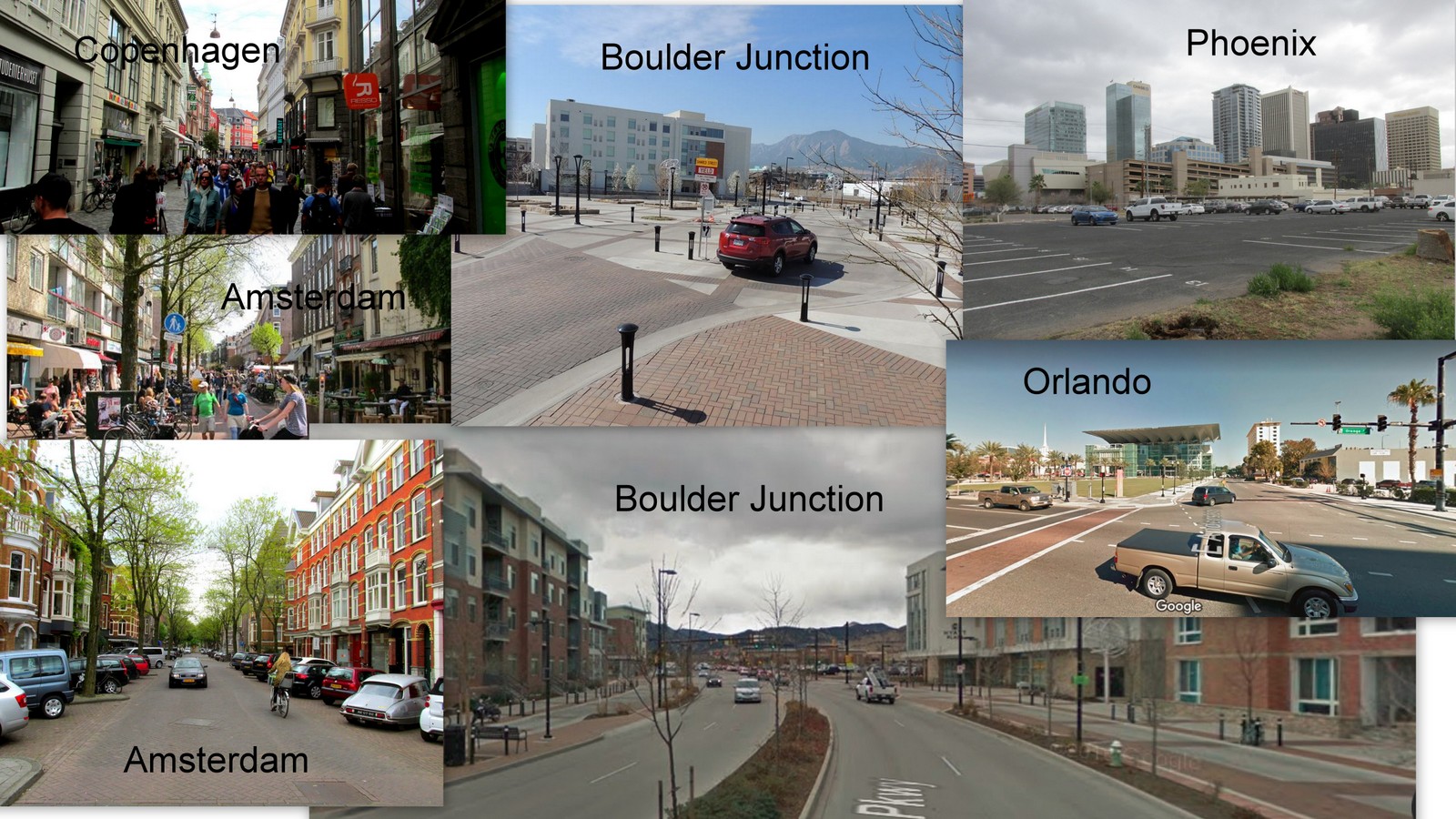

But what Vancouver illustrates to me is, in my experience, almost an iron law of cities or neighborhoods: The older the city or neighborhood, the more human-scaled and charming and walkable and romantic it is. The newer the city or neighborhood, the less one finds those elements.

This illustrates that our generation is failing to leave a quality legacy for future generations (in terms of the places we build). I believe this is largely due to two things that emerged in the 20th Century: the Modernist design paradigm for buildings, and our car-dependent society.

Because cars consume so much space, it has become nearly impossible to create human-scaled, charming places anymore, as cars don’t allow us to do that. Design for motor vehicles is utterly incompatible with design for charm.

It is a tragic dilemma.

Does Vancouver have the ability to make my best-ever list of cities in the future? I believe that because we have built so many modernist, car-happy (i.e., unlovable and unwalkable) places, most all cities in North America will become unaffordable to maintain. The newer cities will be so disliked that we will set about engaging in a lot of demolition – in response to our dislike — and (hopefully) we will have by then regained our senses enough to rebuild such places in a timeless way. In other words, places that are human-scaled and charmingly traditional. Design that we employed for much of civilized history up to the 1940s.

I fear that such a day is a long way off, however. A great deal of economic misery will be required to motivate us in that transformation and restoration.

In sum, I don’t expect Vancouver to make my best-ever city list in my lifetime.

which leads to significant inconvenience when other motorists are in one’s vicinity. You and your neighbors are jostling for elbow room with each of you owning and trying to maneuver a very large metal box. Therefore, such a lifestyle inevitably compels most such people to fight to either stop growth or at least minimize density and building height.

which leads to significant inconvenience when other motorists are in one’s vicinity. You and your neighbors are jostling for elbow room with each of you owning and trying to maneuver a very large metal box. Therefore, such a lifestyle inevitably compels most such people to fight to either stop growth or at least minimize density and building height.