By Dom Nozzi

April 19, 2017

Nothing is more dated than yesterday’s vision of tomorrow. – Unknown

Modern architects recognize 300 masterpieces but ignore the other 30 million [modernist] buildings that have ruined the world. – Andres Duany

Recently, a Boulder CO online newsletter published an essay I had written describing my vision for the redevelopment of the Boulder Community Hospital site (also known as Alpine-Balsam) that the City of Boulder had purchased and was planning to redevelop. Two Boulder friends of mine, who admirably tend to express support for compact, walkable urban design, noted as well to me their support for modernist architectural design in the redevelopment.

It was very disheartening for me to hear of their support for modernism. I believe that modernism would greatly contribute to undermining the potential success of this redevelopment – success that could serve as a model for future development in Boulder.

I prefer traditional design over modernist design.

Some Merits of Traditional Design

Traditional architectural design tends to be much more readily loved by most people. This makes a great deal of sense, since by definition, traditional design has stood the test of time. Not surprisingly, there is a fair amount of research suggesting that traditional architecture, such as Georgian and Victorian terraces and mansion blocks, contributes to our wellbeing. Beauty makes people happy.[1] By contrast, modernist architecture tends to be shocking or repellent to most. Visual preference surveys by Tony Nelessen conducted throughout the nation consistently shows this to be the case.

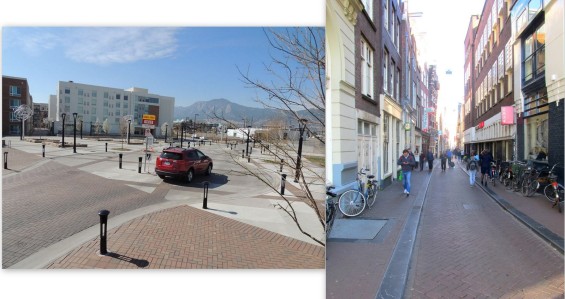

Traditional design tends to be more kind and interesting to pedestrians due to the use of ground floor windows, front-facing entryways, and building ornamentation. By contrast, modernist design has a bad habit of offering sterility and lack of place-making at the ground level.

Throwing Away Timelessness

The Modernist paradigm makes “innovation” the design imperative, which arrogantly assumes that there is no reason a new, untested design cannot reliably achieve admiration and greatness.

Modernists throw away design rules that have stood the test of time in creating buildings that are pleasing and comprehensible to most. Throwing away rules is a recipe for creating incomprehensible, unappealing, unsustainable garbage in the vast majority of cases. It is akin to handing a typewriter to a monkey and expecting the monkey to type out the works of Shakespeare.

Consider this example of a written paragraph, where rules of grammar, spelling, punctuation, consistency in font, and other writing conventions are ignored:

red moss teeaere eeaapoiere STRAIGHT method. Tether: highlight. totalitarian doctrines. Fight, Might. BreaD Moss tree Goofballs. Magnet; Tennis Jodding. Running_____ Break. Slow! Aspirin. Hockey hockey hockey hockey. Shoes and purple. WHISPER### ****&&&&&&@@@@@

An “innovative” paragraph, perhaps, but incomprehensible, utterly ugly, and chaotic.

Note that I do not intend to suggest that architects are as uneducated as monkeys. To the contrary, architects tend to be highly intelligent. But by throwing out time-tested design rules, architects voluntarily blind themselves to design intelligence.

To me, it is exceptionally tragic that modernists are doing to our communities what the above paragraph does to writing. To abandon writing rules, and to abandon the timeless rules of neighborhood design, we abandon what should be (and has been throughout history) the beauty and elegance of the written word, and the beauty and elegance displayed by so many of our historic neighborhoods.

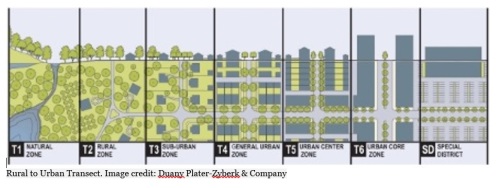

Modernism throws away timeless design in several ways at the neighborhood level. Emily Talen, in her book Neighborhood (2019), notes that the highly influential Congress International Architecture Modern (CIAM) successfully influenced — for decades and to this day — the design of neighborhoods throughout the world so that they included the highly dysfunctional features of separating homes from offices, retail, civic, and manufacturing; prioritizing the car over the pedestrian; rejecting the street as public space; creating superblocks that promote insularity; treating buildings as isolated objects in space rather than as part of a larger interconnected urban fabric; rejecting traditional elements such as squares and plazas; demolishing large areas of the city to make unfettered places for new built forms; and creating enclosed malls and sunken plazas that deaden public space. I would also note that these modernist designers also brought dysfunctional, disconnected, disorienting, curvilinear roads to neighborhoods.

Look the Other Way with Greenwashing

It is quite common for a modernist architect to “green” the design of his or her building by covering much of it with vegetation. Modernists do this to soften the otherwise brutal, sterile nature of their “innovative” designs. By doing so, they leverage the human tendency to love nature and vegetation. “Maybe if I hide my unlovable design behind ivy and shrubs, people will like the appearance of my otherwise distasteful structure!”

High-tech conservation and solar energy methods, similarly, are often used by modernists to gain favor and have people look the other way with regard to the unfortunate, unpleasant building design. “Are you not impressed by my triple platinum LEED-certified building that conserves so much energy?” Pay no attention to the fact that the building looks like Soviet-era brutality.

The Conservation Benefits of Traditional Design

Despite the conventional wisdom that contemporary buildings perform far better than older, traditional buildings when it comes to energy conservation and overall environmental sustainability, it turns out that traditional, older buildings tend to be inherently much more “green” environmentally than modernist building design.

Why?

One reason is that traditional design tends to more often deploy passive conservation methods such as overhanging pitched roofs. Such roofs are much more effective than modernist flat roofs in shedding snow and rain. The traditional pitched roof much more effectively avoids costly moisture leaks from pooled water, or collapse from excessive snow weight. The roof overhang provides shade from a hot sun. Traditional buildings tend to be more appropriately oriented to take advantage of the cooling and heating cycles of the sun throughout the day and in various seasons. Modernist buildings tend to “innovatively” disregard such passive strategies.

Traditional building design also tends to use more durable building materials (such as brick, masonry, and wood), and use locally-sourced materials. This reduces the energy costs of initial cost, maintenance, repair, and replacement. By contrast, modernist buildings tend to use more exotic, difficult to maintain materials such as vast amounts of glass or polished steel.

Because traditional building design is more likely to be loved than modernist design, the building is more sustainable and environmentally friendly simply by the fact that by being lovable, citizens are more likely to want to protect and repair the building, rather than tear it down. The prolific tearing down of modernist buildings we have already seen in great numbers (due in part to their unlovable nature) is extremely costly in terms of energy conservation and environmental conservation. This frequent demolition of modernist buildings is certain to continue in the future.

Modernist Non Sequiturs

To win political and societal support for modernist design, modernist architects frequently use non sequiturs. Modernist buildings are praised for being “progressive” or “optimistic about the future.” Such buildings are called “democratic” or “egalitarian.” By  contrast, traditional buildings are disparaged as being “authoritarian” or “regressive” or “pessimistic.” Traditional buildings are often ridiculed as being “nostalgic” (implying an effort to create a fake historical appearance), or “not forward looking.”

contrast, traditional buildings are disparaged as being “authoritarian” or “regressive” or “pessimistic.” Traditional buildings are often ridiculed as being “nostalgic” (implying an effort to create a fake historical appearance), or “not forward looking.”

Nonsense.

It is entirely inappropriate to associate political or ethical values with building style or design.

Giving Compact Development a Black Eye

Boulder residents have a long, unfortunate history of counterproductively opposing higher-density development with the justification that such development harms Boulder’s small town character, is environmentally destructive, or creates traffic and parking congestion.

Ironically, it is low-density development that is more responsible for such problems.

The essential need to shift Boulder’s politics toward support for more compact development shows why it is extremely important that compact, walkable, higher-density buildings be lovable in design. Using more lovable traditional design is a powerful way to gain more acceptance of compact design in Boulder. A great many people in Boulder dislike compact development because it is associated with “boxy” or “monolithic” or “sterile” buildings. The last thing Boulder needs is for ugly buildings to give compact development a black eye. Modernist buildings are also infamous for not fitting in with the context of their location (an inherent problem when “innovation” is the key design objective). Each of these traits are typical of a modernist building, whereas a traditional building is more likely to feel friendly or compatible in or near existing neighborhoods.

Traditionally designed neighborhoods tend to be unified in style and follow a design pattern. By being more compatible and lovable, traditional buildings are much better able to gain neighborhood and community acceptance when the project is more dense or compact. By contrast, modernist design theory, again, tends to celebrate “eclectic” and “innovative” design. Such design ignores context and tends to feel disconcertingly chaotic, incompatible, and bizarre. This is a surefire recipe for amplifying neighborhood opposition. “There are…reasons that more British cities are not beautiful. Firstly, there are the architects themselves, who tend to prefer innovative buildings over traditional ones.”[2]

The Absence of Mimicking Modernism

It is quite telling that in Boulder, as elsewhere, there are zero neighborhoods which people look upon with affection that are mostly or entirely modernist (similarly, I know of no predominantly modernist towns or neighborhoods that are tourist destinations). As John Torti, principal of Torti Gallas & Partners, has stated, “…could you imagine an entire city made out of Frank Gehry buildings? There’s a notion of the monument versus the fabric. Michael Dennis called it hero buildings versus soldier buildings. In most New Urbanist practices we create the soldier buildings, the fabric buildings that make cities.”[3]

But there are many examples of admired neighborhoods in Boulder that are primarily traditional: Mapleton Hill, Iris Hollow, Dakota Ridge, Washington Square, and Holiday.

The Rejection of Context

The modernist paradigm is focused on creating individualistic “statement” buildings that have no relation to their neighbors. Context, pattern, time-tested design, rules, and fabric are tossed into the waste can. Instead, the focus is on innovation, which tends to result in odious, unlovable buildings that almost never draw affection – particularly when modernist buildings are grouped together in a neighborhood (is it even possible to group together “statement” buildings into a coherent whole?) Instead, modernist buildings are parasitically, invasively, and incrementally added into an existing traditional neighborhood, allowing the modernist building to piggyback on the affection for the traditional neighborhood.

Torti notes that:

“The notion of understanding and respecting the traditional city—rather than showing off a particular site or building—is the essential difference. Christopher Alexander, the great planning and architectural theorist, says it in a very poignant way. When you come to a place, a city, or a site, you must look and try to understand the whole place. It sums up what I think new urbanists are all about, which is being humble enough when we work on buildings to let the city take preference.”[4]

Similarly, Stefanos Polyzoides, principal of Moule & Polyzoides, Architects and Urbanists, says that

“…the prime ingredient of urbanism is really public space and the public realm. So the urban plan comes first and the building second. It becomes an issue of whether the building is a monument or a piece of fabric. Then does this building dominate what’s in place or does this building add to it or transform it? New urbanists essentially believe in compatibility between building and place, in the sense that buildings having specific intentions when placed in a particular location in the urban fabric.”[5]

Incrementally Destroying Affection

Tragically, over time, this incremental invasion by modernist buildings erodes the affection felt for the traditional neighborhood as it slowly loses its charm to the invader buildings. Each modernist building added to a traditional neighborhood is a new blight on the neighborhood, and the neighborhood takes another step toward being unloved.

Modernist buildings, by design, stick out like a sore thumb. They take pride in the amount of shock value they induce. They thumb their nose at conventions and timeless design and fitting into a context. A modernist building tends to call attention to itself,  which is most unfortunate for the neighborhood, as the modernist design is so commonly wretched.

which is most unfortunate for the neighborhood, as the modernist design is so commonly wretched.

There is a reason that modernists fear and oppose visual preference surveys. Their modernist designs always fail to gain support. The modernist excuse for this? “Citizens are too stupid or lacking in architectural knowledge to realize that the modernism was brilliant and beautiful!”

Rubbish.

I wrote this blog on the unpopularity of modernism.

Repetition and Making Lovable, Compatible Design Illegal

It is said, rightly, that imitation is the highest form of flattery. When a building design stands the test of time and is loved for many generations, it is natural and desirable that it be mimicked by new buildings. Traditional buildings, by definition, have long been  loved and should therefore become a pattern that should be followed by new buildings. Tellingly, the chaotic, no-rules modernist building tends to NEVER be replicated. I know of no examples.

loved and should therefore become a pattern that should be followed by new buildings. Tellingly, the chaotic, no-rules modernist building tends to NEVER be replicated. I know of no examples.

One of the things we tend to love is a city that shows order, repetition, balance, and symmetry. Without an emphasis on repetition, it seems chaotic, like no one is in charge, which is disconcerting. Diversity and variety should be introduced gently so as not to take away from an overall design pattern (such as building height or shape). Variety might be introduced through differences in fencing style, color, or cornice, for example.

Much of Pearl Street Mall is a good example of lovable repetition with a dash of variety.

Given all of this, it is an atrocity that in America, communities have been saddled for several decades by federal historic preservation guidelines that REVERSE this time-honored method I have just summarized. In historic neighborhoods full of lovable, charming historic buildings, the federal historic preservation guidelines PROHIBIT additions to existing traditional buildings that mimic or are even compatible with the existing traditional building style. Instead – insanely – the federal guidelines REQUIRE that the addition to an existing historic and traditional building be “of its time.” Today, since “of its time” buildings happen to be unlovable modernist buildings, federal historic preservation rules make it mandatory that lovable historic buildings be degraded in all their charm and glory by being appended by a hideous modernist abomination.

Most modernist architects proudly – triumphantly – design “of its time” modernist buildings when new buildings are to be built in a traditional historic neighborhood.

Who needs enemies when we have ourselves?

What does it say about a society when it requires new construction to only use a failed, unlovable building design? Modernist architecture is, after all, a failed paradigm. We are now obligated to keep adding more and more failure to our neighborhoods so that the construction is “of its (failed) time.”

Today, it tends to be that only arrogant, elitist, pompous modernist architects who have “drank the Kool Aid” admire modernist buildings. The rest of us are too stupid to realize the brilliance of modernist buildings.

Unfortunately for me, it would seem that nearly all architects who design buildings in Boulder prefer modernist design, which makes it extremely likely that modernist design will once again be the dominant (exclusive?) design at the hospital site being redeveloped.

I believe that more modernist building design is likely to meet with strong citizen opposition to the redevelopment of the hospital site, thereby undermining this golden opportunity to have the City show how compact development is properly and popularly done.

Affordability and Jobs?

Having said all of this, there are one or two advantages to modernist buildings. First, they are so strongly disliked by so many people that they will therefore not see a significant increase in price over time. They will not retain their value. Or, if there is an appreciation in housing value in the community, the appreciation for modernist homes will be lower than the appreciation that traditional buildings will see. Very few people will be interested in buying a home that seems so dated and so bizarre, which will put downward pressure on the price of the home. Because modernist homes will be so difficult for an owner to sell, such homes will be relatively affordable to lower income people who don’t have much choice about how attractive their homes might be.

A study from the Netherlands showed that ‘even controlling for a wide range of features, fully neo-traditional houses sell for 15 per cent more than fully non-traditional houses…London terraced houses built before the First World war went up in value by 465 per cent between 1983 and 2013, compared to 255 per cent for post-war property of the same type. Beauty sells, but because it’s rare, it’s exclusive.[6]

So providing more affordable housing in an expensive housing market is one benefit.

Another benefit is that because modernist buildings tend to be so unlovable to the vast majority of people, modernist buildings will provide more jobs in future years because they will be more frequently demolished and in need of reconstruction to other buildings.

Time to Sunset Modernism

It is far past time that America end its failed architectural experiment of modernism. The modernist paradigm has destroyed lovability throughout the nation, and has bred widespread cynicism about our ability to create buildings worthy of our affection.

Our quality of life and any hope of civic pride depends on our returning to the tradition of using time-tested building design.

Don’t miss this critique of contemporary building design: “…for thousands of years, nearly every buildings humans made was beautiful. It is simply a matter of recovering old habits. We should ask ourselves: why is it that we can’t build another Prague or Florence? Why can’t we build like the ancient mosques in Persia or the temples in India? Well, there’s no reason why we can’t…”

https://www.currentaffairs.org/2017/10/why-you-hate-contemporary-architecture

Other Blogs I Have Written Regarding Modernist Architecture

The Failure of Modernist Architectural Design

https://domz60.wordpress.com/2019/06/04/the-failure-of-modernist-architectural-design/

The Failure and Unpopularity of Modernist Architecture

The Failure and Unpopularity of Modernist Architecture

Modernist Cult of Innovation is Destroying Our Cities

https://domz60.wordpress.com/2017/01/24/the-modernist-cult-of-innovation-is-destroying-our-cities/

Opposition to More Housing

https://domz60.wordpress.com/2019/02/19/opposition-to-more-housing-or-better-urbanism/

Moses and Modernism and Motor Vehicles

https://domz60.wordpress.com/2018/12/18/moses-and-modernism-and-motor-vehicles/

Indirect Opposition to Affordable Housing

The Indirect Opposition to Affordable Housing in Boulder, Colorado

Citations

[1] West, Ed. “Classical architecture makes us happy. So why not build more of it?”, The Spectator. March 15, 2017.

[2] West, Ed. “Classical architecture makes us happy. So why not build more of it?”, The Spectator. March 15, 2017.

[3] https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2017/03/09/great-idea-architecture-puts-city-first

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] West, Ed. “Classical architecture makes us happy. So why not build more of it?”, The Spectator. March 15, 2017.

contrast, traditional buildings are disparaged as being “authoritarian” or “regressive” or “pessimistic.” Traditional buildings are often ridiculed as being “nostalgic” (implying an effort to create a fake historical appearance), or “not forward looking.”

contrast, traditional buildings are disparaged as being “authoritarian” or “regressive” or “pessimistic.” Traditional buildings are often ridiculed as being “nostalgic” (implying an effort to create a fake historical appearance), or “not forward looking.”

which is most unfortunate for the neighborhood, as the modernist design is so commonly wretched.

which is most unfortunate for the neighborhood, as the modernist design is so commonly wretched. loved and should therefore become a pattern that should be followed by new buildings. Tellingly, the chaotic, no-rules modernist building tends to NEVER be replicated. I know of no examples.

loved and should therefore become a pattern that should be followed by new buildings. Tellingly, the chaotic, no-rules modernist building tends to NEVER be replicated. I know of no examples.

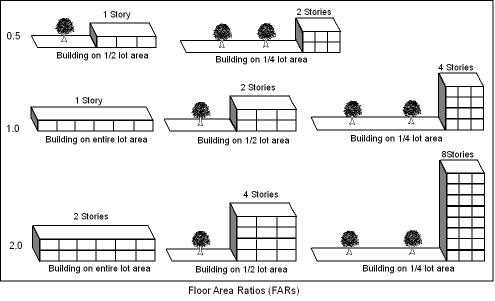

and timeless traditional building design into the waste can in favor of repellent, “innovative,” look-at-me design. Citizens are thereby conditioned to equate new compact development with hideous buildings. Second, local zoning regulations in cities such as Boulder have made lovable, human-scaled design illegal by requiring excessive setbacks, excessive car parking, and excessive private open space. Third, nearly all citizens live car-dependent lifestyles. And because their cars consume such an enormous amount of space, motorists are compelled to fear and oppose town design that they otherwise love as tourists. They have, in essence, become their own enemies by striving to improve their life as motorists (equating quality of life with easy parking and free-flowing traffic), not realizing that doing so is ruinous to a healthy city and a lovable quality of life.

and timeless traditional building design into the waste can in favor of repellent, “innovative,” look-at-me design. Citizens are thereby conditioned to equate new compact development with hideous buildings. Second, local zoning regulations in cities such as Boulder have made lovable, human-scaled design illegal by requiring excessive setbacks, excessive car parking, and excessive private open space. Third, nearly all citizens live car-dependent lifestyles. And because their cars consume such an enormous amount of space, motorists are compelled to fear and oppose town design that they otherwise love as tourists. They have, in essence, become their own enemies by striving to improve their life as motorists (equating quality of life with easy parking and free-flowing traffic), not realizing that doing so is ruinous to a healthy city and a lovable quality of life. development, largely due to the modernist architectural paradigm, local car-friendly development regulations, and car-dependent citizens who have become cheerleaders for their cars rather than for themselves, their family, and their neighbors.

development, largely due to the modernist architectural paradigm, local car-friendly development regulations, and car-dependent citizens who have become cheerleaders for their cars rather than for themselves, their family, and their neighbors.

LOT more cars. What an irony, since NIMBYs HATE more crowded roads and parking lots.

LOT more cars. What an irony, since NIMBYs HATE more crowded roads and parking lots. Abbey once said, it’s not the beer cans I mind – it’s the roads.

Abbey once said, it’s not the beer cans I mind – it’s the roads.